|

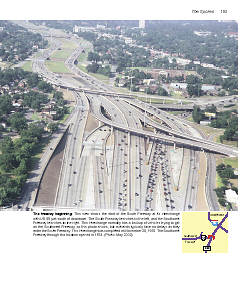

Chapter 4: The Spokes

|

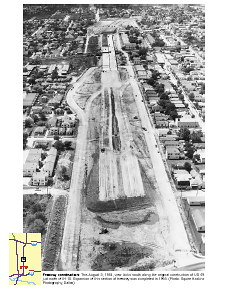

||

|

|

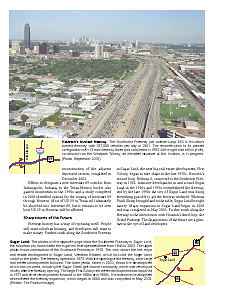

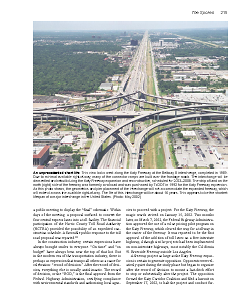

In the world of the loop and radial freeway system, downtown is the center of the universe. Call it the hub. Houston’s eight spokes converging on downtown are just about the limit of what a downtown freeway interchange system can handle. But as space opens away from downtown, the next tier of six spokes takes root, mostly along Loop 610. Even the Beltway gives birth to a spoke. Houston’s system of spokes is one of the most extensive and well-balanced among the major cities in the United States. |

|

|

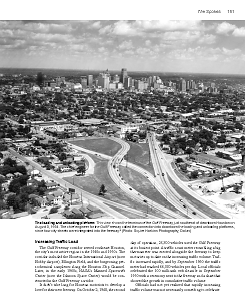

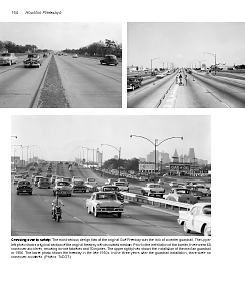

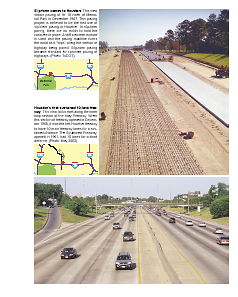

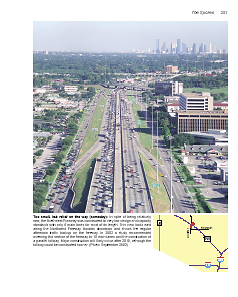

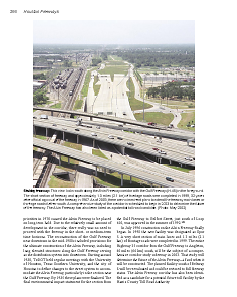

The Gulf Freeway launched Houston into the freeway era on September 30, 1948. As the history of the Gulf Freeway unfolded, it became a classic story of the rise of the American urban freeway and the myriad of issues that would accompany it. Intertwined in the story of the Gulf Freeway is the demise of the urban electric railway, the unprecedented demand for new freeways in the postwar era, huge suburban development, malls, traffic jams, the development of better freeways, urban protest, and the never-ending battle to catch up to demand. The newly dedicated Gulf Freeway was ahead of its time, yet it couldn’t keep up with the times. It would be brought into the modern era, not just once, but twice. |

|

|

|

|

|

With the freeway now in service, it quickly became apparent that something was missing: the freeway had no name. Press reports called it the Interurban Expressway, referring to the Galveston-Houston interurban railway that previously occupied the corridor. Mayor Holcombe quickly took action to solve the problem and launched a contest to name the freeway. There was no shortage of suggestions. The six judges sifted through 86 pages with the 13,000 entries, and on December 17, 1948, the winner was announced. The freeway would be named the Gulf Freeway. The exact name “Gulf Freeway” was suggested by only one entry, that of Miss Sara Yancy of the Heights. She received a $100 prize and, perhaps more importantly, placed her mark on Houston’s freeway system. |

|

|

|

|

|

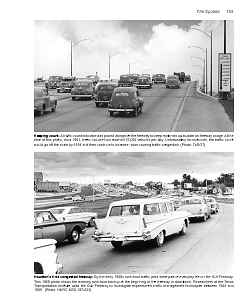

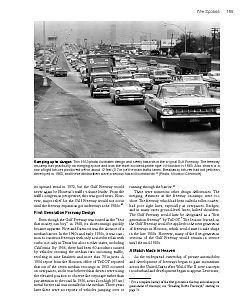

It didn’t take long for Houston motorists to develop a love for their new freeway. On October 2, 1948, the second day of operation, 28,800 vehicles used the Gulf Freeway at its busiest point. A traffic count meter resembling a big thermometer was erected alongside the freeway to keep motorists up to date on the increasing traffic volume. Traffic increased rapidly, and by September 1950 the traffic meter had reached 66,300 vehicles per day. Unfortunately for motorists, the traffic count would go off the meter scale by 1954 and then continue to increase, soon causing traffic congestion. |

|

|

|

|

|

Freeways and shopping malls were a match made in heaven, so it was only a matter of time before the Gulf Freeway would get its first mall. In March 1954 ground was broken for Gulfgate Shopping City, an open-air mall located at the intersection of the Gulf Freeway and the planned South Loop. The grand opening of Gulfgate Shopping City and its 62 stores took place on September 20, 1956. A huge crowd converged on the shopping center opening day, and Gulfgate Shopping City was highly successful. |

|

|

While the space program was pushing science and technology to new levels, five of the astronauts had a more down-to-earth interest: fast cars. Gordon Cooper, Gus Grissom, Walter Shirra, Alan Shepherd, and Scott Carpenter were all automobile enthusiasts. Two in particular, Cooper and Grissom, were especially fanatical about auto racing and were partners in an Indy car racing team that participated in major racing events. The racing enthusiasts didn’t limit their speed contests to the race track. The roads around NASA, especially the Gulf Freeway and State Highway 3, were the scene of frequent high-speed races between the astronauts. |

|

|

"Like the pyramids of Egypt, the freeway has consumed much of the working careers of many of the workers involved in its construction." -Houston Post, 1976 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

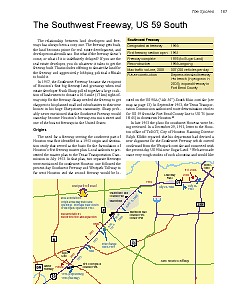

The relationship between land developers and freeways has always been a cozy one. The freeway gets built, the land becomes prime for real estate development, and developers make millions. But what if the freeway doesn’t come, or what if it is indefinitely delayed? If you are the real estate developer, you do whatever it takes to get the freeway built. That includes offering to donate the land for the freeway and aggressively lobbying political officials to build it. In 1957 the Southwest Freeway became the recipient of Houston’s first big freeway land giveaway when real estate developer Frank Sharp pulled together a large coali-tion of landowners to donate a 10.5-mile (17 km) right-of-way strip for the freeway. |

|

|

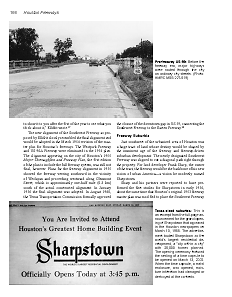

Just southwest of the urbanized area of Houston was a huge tract of land whose destiny would be shaped by the imminent age of the freeway and freeway-driven suburban development. The newly designated Southwest Freeway was aligned to cut a diagonal path right through the property. For land developer Frank Sharp, the owner of the tract, the freeway would be the backbone of his new vision of urban America—a vision he modestly named Sharpstown. |

|

|

|

|

|

The BMW 600 was an enlarged version of the Motocoupe, a popular minicar of the 1950s that originated with the Italian company Iso in 1953 and was licensed to numerous automobile manufacturers, including BMW in Germany. What was believed to be the first Motocoupe in the United States arrived at the Port of Houston in late 1956 and was put on display in the lobby of the Houston Bank and Trust Company. The 772-pound (350 kg) Motocoupe had an air-cooled one-cylinder motorcycle engine capable of speeds up to 60 miles per hour (96 km/h). The BMW 600 was slightly larger than the Motocoupe, weighing about 1140 pounds (515 kg). Notice that the Motocoupe and BMW 600 do not have driver-side doors. The front panel of the vehicles including the steering wheel hinged open to let the driver in. |

|

|

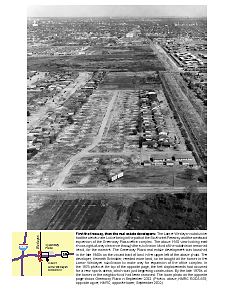

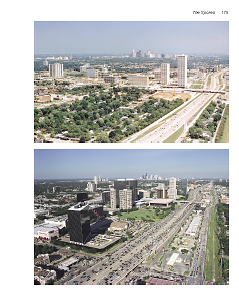

The Lamar Weslayan subdivision had the unfortunate luck of being in the path of the Southwest Freeway and the westward expansion of the Greenway Plaza office complex. Most of the subdivision remained intact, for the moment, when the freeway was built in the early 1960s. The Greenway Plaza real estate development was launched in the late 1960s. The developer, Kenneth Schnitzer, needed more land, so he bought all the homes in the Lamar Weslayan subdivision to make way for expansion of the office complex. By the late 1970s all the homes in the neighborhood had been removed. |

|

|

|

|

|

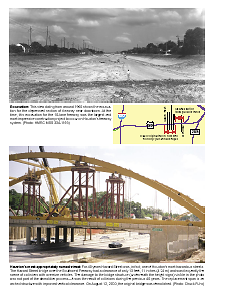

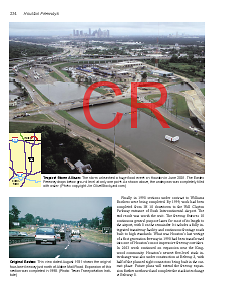

When the storm hit in June 2001, it un-leashed a major freeway flood event in Houston and filled the Southwest Free-way trench nearly to ground level. At that time, construction was in progress to widen the trench. Most motorists were able keep their vehicles out of the water, but the construction contractor, Williams Brothers Construction, wasn’t so lucky. It lost 42 pieces of equipment, including 22 pieces of machinery (including large cranes, such as the one shown in the lower photo), 17 trucks, and 3 message boards. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

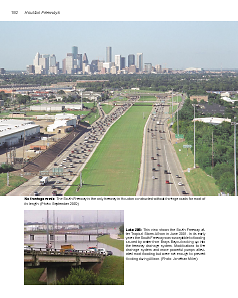

But just as the South Freeway represented the vision of the freeway of the future, it would also be intertwined with perhaps the most dramatic story in the history of race relations in Houston. It’s a story of integration, white flight, and urban transformation. And it’s a story where the South Freeway would have the final word, at least in terms of ground zero for the events that would unfold over a 15-year period. |

|

|

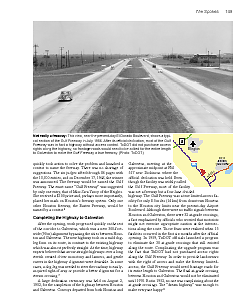

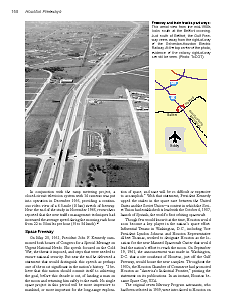

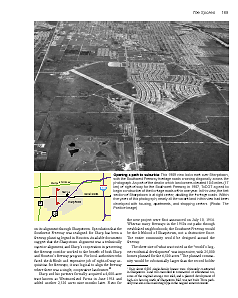

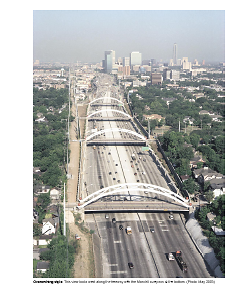

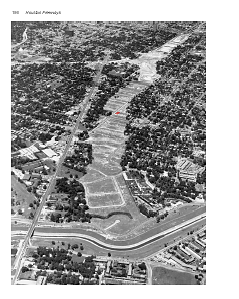

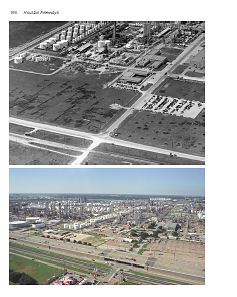

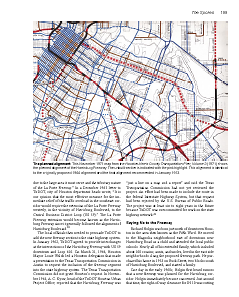

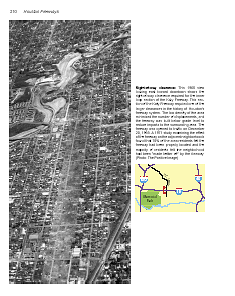

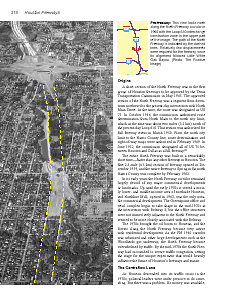

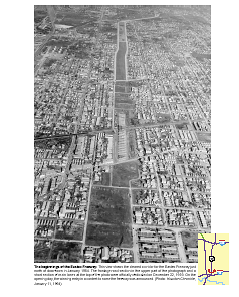

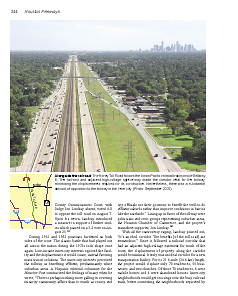

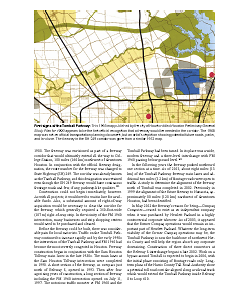

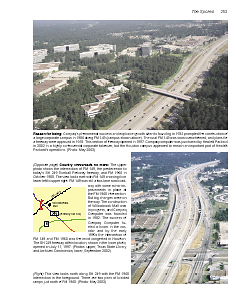

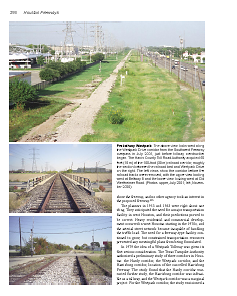

This view shows the South Freeway corridor in June 1972, looking north. Right-of-way clearance had begun in the late 1960s and was nearly complete at the time of this photo. The location of Jack Caesar’s house at the southeast corner of Wichita and Hutchins is indicated in red, and is now approximately in the center of the freeway. Caesar’s house became a flash point for racial integration in Houston in 1952 when Caesar and his family became the first blacks to move into the all-white, heavily Jewish Riverside Terrace neighborhood. In April 1953, a bomb exploded on Caesar’s front porch. The bomb caused only minor property damage and no injuries, but it launched full-scale white flight from the Riverside Terrace neighborhood. |

|

|

The South Freeway corridor sat vacant for more than five years due to funding shortfalls at TxDOT. The existence of such a wide corridor of clear land so close to the central business district for most of the 1970s was a remarkable novelty and is something that will probably never again be seen in any city in the United States in the context of freeway construction. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

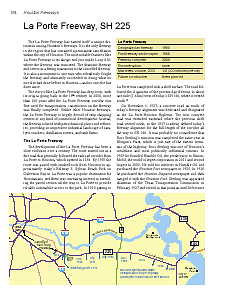

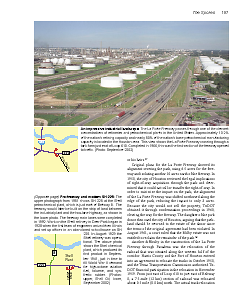

The La Porte Freeway has earned itself a unique distinction among Houston’s freeways. It is the only freeway in the region that has sustained a permanent cancellation within the city of Houston. The most notable feature of the La Porte Freeway is its abrupt end just inside Loop 610, where the freeway was truncated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The freeway was coming back to life, and Richard Holgin was ready for it. He was determined to do everything he could to stop the freeway, and he was now empowered by NEPA and other new regulations that gave commu-nities a large voice in the process. |

|

|

In the final analysis, it can be concluded that insufficient highway construction funding was the principal cause of the demise of the Harrisburg Freeway. But when the freeway’s future became tenuous due to the funding situation, Richard Holgin’s opposition probably was the decisive factor in the ultimate decision to abandon the freeway. Had there been no opposition or if there had been visible community support, the Harrisburg Freeway prob-ably would have moved forward, slowly but surely. |

|

|

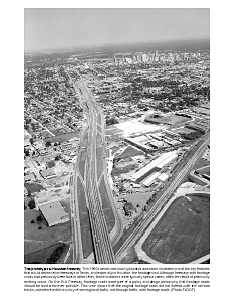

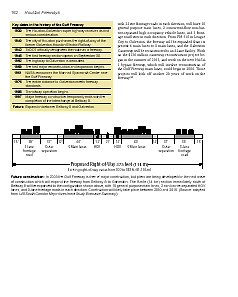

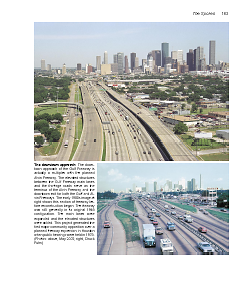

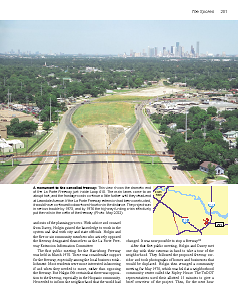

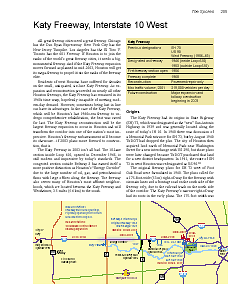

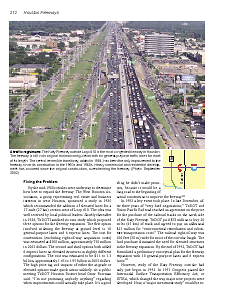

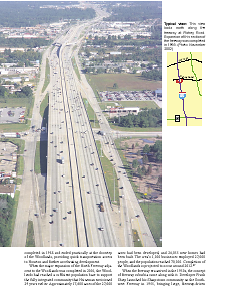

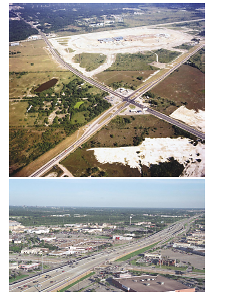

All great freeway cities need a great freeway. Chicago has the Dan Ryan Expressway. New York City has the New Jersey Turnpike. Los Angeles has the El Toro Y. Toronto has the 401 Freeway. If Houston is to join the ranks of the world’s great freeway cities, it needs a big, monumental freeway. And if the Katy Freeway expansion moves forward as planned in mid-2003, Houston will get its mega-freeway to propel it into the ranks of the freeway elite. |

|

|

In the early days of the Katy Freeway’s development outside Loop 610, there was a dispute between the two highest-ranking TxDOT managers in the Houston district about the required corridor width for the freeway. Wiley Carmichael, who managed projects outside of Loop 610, wanted to construct IH 10 within the available US 90 right-of-way, while A. C. Kyser, who managed the Houston Urban Project Office and was responsible for projects inside Loop 610, recommended a wider corridor. The project was under the jurisdiction of Carmichael and he got his way, but the use of the narrow corridor proved to be very costly to Houston in the long run, necessitating a large and costly right-of-way clearance for the planned expansion and delaying the project about 25 years after it was needed. |

|

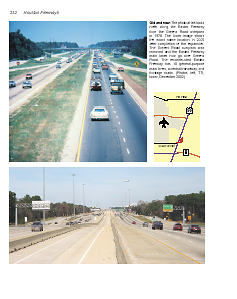

|

While A. C. Kyser’s 10-lane inner loop section of the Katy Freeway was well-designed to take care of traffic needs far into the future, Wiley Carmichael’s underdesigned section outside Loop 610 soon became overwhelmed with traffic and eventually degenerated into Houston’s worst traffic nightmare. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

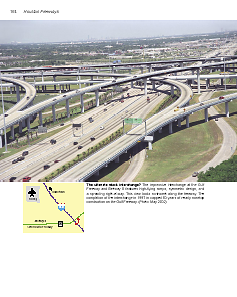

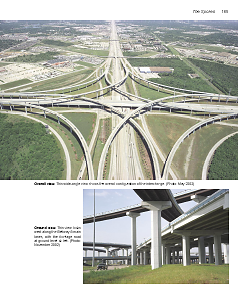

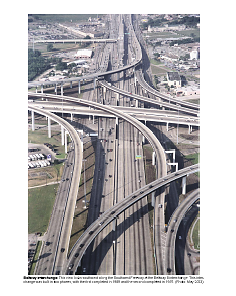

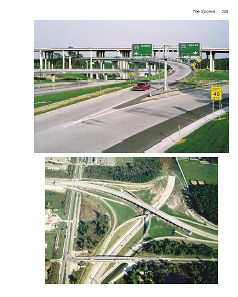

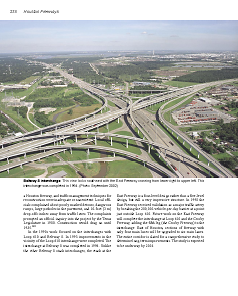

The interchange, completed in 1989, will be dismantled and rebuilt during the Katy Freeway expansion and reconstruction, scheduled for 2003–2008. The life of this interchange will be about 16 years. This appears to be the shortest lifespan of a major interchange in the United States. |

|

|

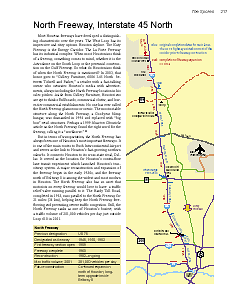

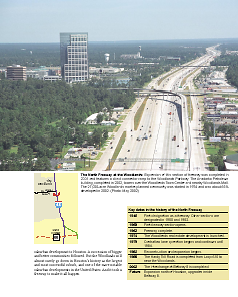

Houstonians are apt to think of billboards, commercial clutter, and lower-tier commercial establishments when the North Freeway is mentioned. No one has ever called the North Freeway glamorous or scenic. The most notable structure along the North Freeway, a Goodyear blimp hangar, was dismantled in 1994 and replaced with “big box” retail structures. Perhaps a 1999 Houston Chronicle article on the North Freeway found the right word for the freeway, calling it a "workhorse." |

|

|

Something fast and cheap was needed to help relieve the traffic congestion on the North Freeway, and the contraflow lane met both those requirements. It took away the inside traffic lane from the non-peak traffic direction, using it for buses and vanpools traveling in the peak direc-tion. The contraflow lane was separated from oncoming traffic only by pylons spaced at 40-foot (12 m) intervals. There was no barrier. |

|

|

The contraflow lane ended its five-year run on November 23, 1984, when traffic was shifted to a central barrier-separated lane. By that time, planning was well underway for an extensive transitway system on Houston’s freeways—a system that was inspired and influenced by the success of the North Freeway contraflow lane. |

|

|

Originally opened in 1974, the Woodlands received numerous national and international awards for its responsible and innovative design. Suburban home buyers have made the Woodlands Houston’s perennial leader in new home starts through most of the 1980s and 1990s, and continuing through 2003. The Woodlands will almost surely go down in Houston’s history as the largest and most successful suburb, and one of the more notable suburban developments in the United States. And it took a freeway to make it all happen. |

|

|

|

|

|

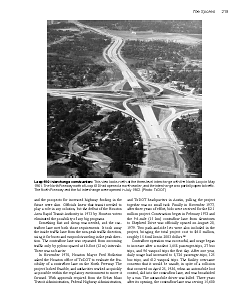

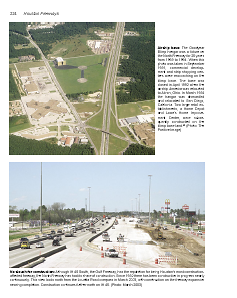

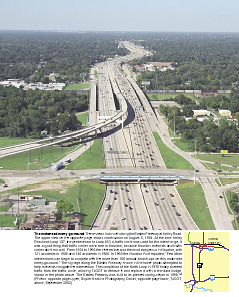

Clearing out the old and bringing in the new is a regular event on Houston’s freeways, but sometimes the transformation is especially satisfying. In the case of the Eastex Freeway, the “old” was the original, antiquated 1950s-era design, Houston’s last vestige of a first generation freeway. The “new” is a state-of-the-art freeway, among the best in Houston. Getting from old to new was a particularly long and painful process due to the seemingly interminable delays during construction, but by the late 1990s Eastex Freeway motorists were finally driving on their new freeway. After the transformation was complete, there was surely no doubt: new is better. |

|

|

|

|

|

"The Eastex Freeway widening has been a theater of the glacial." -Houston Chronicle, April 26, 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

CR=copyrighted image, reproduction or use prohibited |

|

|

|

|

|

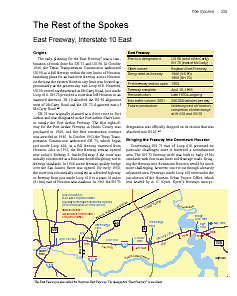

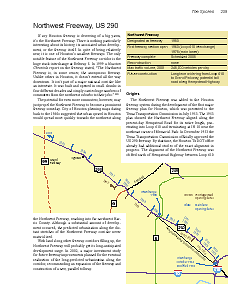

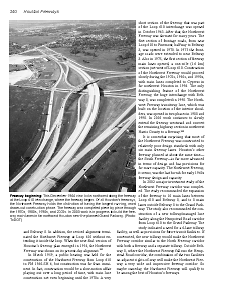

If any Houston freeway is deserving of a big yawn, it’s the Northwest Freeway. There is nothing particularly interesting about its history, its associated urban development, or the freeway itself. In spite of being relatively new, it is one of Houston’s smallest freeways. The only notable feature of the Northwest Freeway corridor is the huge stack interchange at Beltway 8. In 1999 a Houston Chronicle report on the freeway stated, “The Northwest Freeway is, in some senses, the anonymous freeway. Unlike others in Houston, it doesn’t extend all the way downtown. It isn’t part of a major national corridor like an interstate. It was built and opened in small chunks in four different decades and simply carries huge numbers of commuters from the northwest suburbs to their jobs.” |

|

|

|

|

|

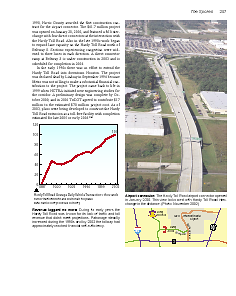

If any major transportation facility in Houston can be attributed to the efforts of one individual, it is the Hardy Toll Road. Jon Lindsay made this project happen. Not only did then Harris County Judge Lindsay make the Hardy Toll Road happen, but he did it in the face of substantial opposition to the project. Building an all-new, limited-access transportation facility is a big accomplishment in the modern era. Doing it nearly single-handedly is even more impressive. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

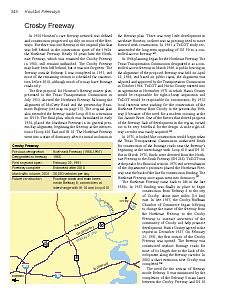

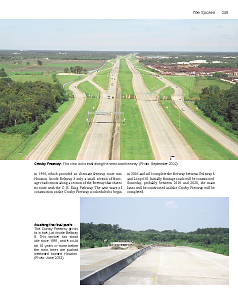

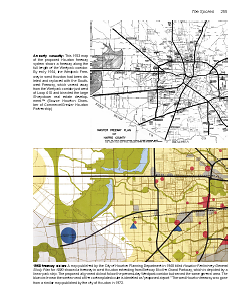

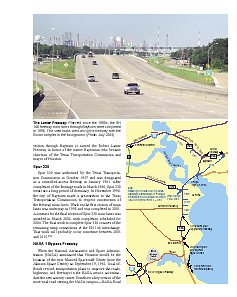

In 1954 Houston’s core freeway network was defined and construction progressed quickly on most of the freeways. But there was one freeway in the original plan that was left behind in the construction spurt of the 1960s: the Northeast Freeway. Nearly 50 years later the Northeast Freeway, which was renamed the Crosby Freeway in 1988, still remains unfinished. The Crosby Freeway may have been left behind, but it was not forgotten. The freeway outside Beltway 8 was completed in 1991, and most of the remaining section is scheduled for construction before 2010, although much of it may have frontage roads only. |

|

|

In May 1988 a group of Houston’s key transportation policymakers met secretly in a downtown conference room. One after another, the top officials committed millions of dollars to a new transportation initiative to benefit a key local interest. An hour and a half later, when the dealing was done, $235 million had been put on the table. Included in the bag of goodies was acceleration of a brand-new, $253 million freeway. |

|

|

|

|

|

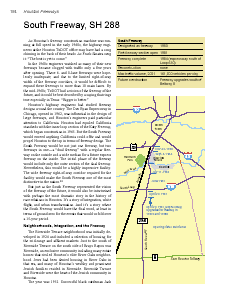

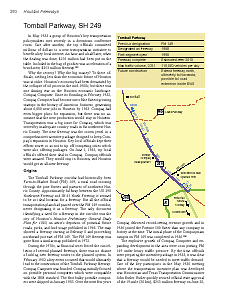

Fifty-one years after the Westpark Freeway was first drawn on the master plan map, motorists will take their first drive on the Westpark Tollway. |

|

|

|

|

|

Negotiations between HCTRA and Metro continued into 1999. Finally in September 1999, a deal was reached. Metro would sell a 50-foot (15 m) strip of the Westpark corridor, half of the 100-foot (30 m) corridor width, to HCTRA. HCTRA would pay $14.3 million for 13 miles (21 km) of the 50-foot strip. Metro would retain 50 feet for future transit use, which was envisioned as a light rail line. On November 18, 1999, the Metro board of directors formally approved the land sale. The Westpark Tollway would be built. |

|

|

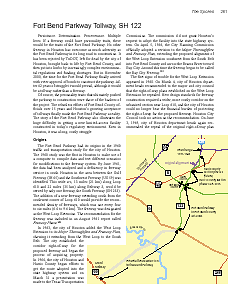

Persistence. Determination. Perseverance. Multiple lives. If a freeway could have personality traits, these would be the traits of the Fort Bend Parkway. No other freeway in Houston has overcome as much adversity as the Fort Bend Parkway in its long road to construction. It has been rejected by TxDOT, left for dead by the city of Houston, brought back to life by Fort Bend County, and then put into limbo by increasingly complex environmental regulations and funding shortages. But in November 2000, the time for the Fort Bend Parkway finally arrived with voter approval of bonds to construct the parkway. After 42 years of struggle it would prevail, although it would be a tollway rather than a freeway. |

|

|

|

|

|

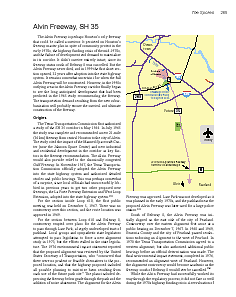

The Alvin Freeway is perhaps Houston’s only freeway that could be called a survivor. It persisted on Houston’s freeway master plan in spite of community protest in the early 1970s, the highway funding crisis of the mid-1970s, and the failure of development and demand to materialize in its corridor. It remains somewhat uncertain if or when the full Alvin Freeway will be constructed. However, new suburbanization in the freeway corridor will probably ensure the survival and ultimate construction of the freeway. |

|

|

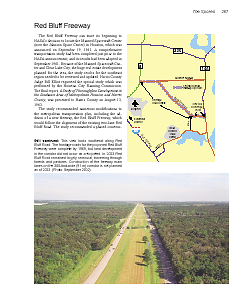

The frontage roads for the proposed Red Bluff Freeway were complete by 1969, but land development in the corridor did not occur as anticipated. In 2003 Red Bluff Road remained largely semirural, traversing through forests and pastures. Construction of the freeway main lanes on the 300-foot-wide (91 m) corridor is not planned as of 2003. |

|

|

|

|

|

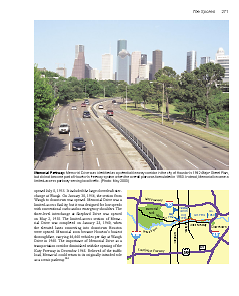

Approximately 45 years after the original announcement of the NASA space center, the principal road serving NASA will finally be brought into the modern era. It was a long wait, but the end result will be a new freeway for Houston. |

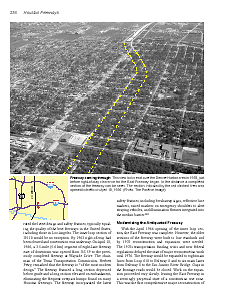

| Continue to next chapter | Home | |